| src | ||

| .gitignore | ||

| .travis.yml | ||

| appveyor.yml | ||

| CHANGES.rst | ||

| HACKING | ||

| LICENSE | ||

| magick.py | ||

| MANIFEST.in | ||

| README.md | ||

| screenshot.png | ||

| setup.cfg | ||

| setup.py | ||

| test.sh | ||

| test_comp.sh | ||

| tox.ini | ||

img2pdf

Lossless conversion of raster images to PDF. You should use img2pdf if your priorities are (in this order):

- always lossless: the image embedded in the PDF will always have the exact same color information for every pixel as the input

- small: if possible, the difference in filesize between the input image and the output PDF will only be the overhead of the PDF container itself

- fast: if possible, the input image is just pasted into the PDF document as-is without any CPU hungry re-encoding of the pixel data

Conventional conversion software (like ImageMagick) would either:

- not be lossless because lossy re-encoding to JPEG

- not be small because using wasteful flate encoding of raw pixel data

- not be fast because input data gets re-encoded

Another advantage of not having to re-encode the input (in most common situations) is, that img2pdf is able to handle much larger input than other software, because the raw pixel data never has to be loaded into memory.

The following table shows how img2pdf handles different input depending on the input file format and image color space.

| Format | Colorspace | Result |

|---|---|---|

| JPEG | any | direct |

| JPEG2000 | any | direct |

| PNG (non-interlaced) | any | direct |

| TIFF (CCITT Group 4) | monochrome | direct |

| any | any except CMYK and monochrome | PNG Paeth |

| any | monochrome | CCITT Group 4 |

| any | CMYK | flate |

For JPEG, JPEG2000, non-interlaced PNG and TIFF images with CCITT Group 4 encoded data, img2pdf directly embeds the image data into the PDF without re-encoding it. It thus treats the PDF format merely as a container format for the image data. In these cases, img2pdf only increases the filesize by the size of the PDF container (typically around 500 to 700 bytes). Since data is only copied and not re-encoded, img2pdf is also typically faster than other solutions for these input formats.

For all other input types, img2pdf first has to transform the pixel data to make it compatible with PDF. In most cases, the PNG Paeth filter is applied to the pixel data. For monochrome input, CCITT Group 4 is used instead. Only for CMYK input no filter is applied before finally applying flate compression.

Usage

The images must be provided as files because img2pdf needs to seek in the file descriptor.

If no output file is specified with the -o/--output option, output will be

done to stdout. A typical invocation is:

$ img2pdf img1.png img2.jpg -o out.pdf

The detailed documentation can be accessed by running:

$ img2pdf --help

Bugs

-

If you find a JPEG, JPEG2000, PNG or CCITT Group 4 encoded TIFF file that, when embedded into the PDF cannot be read by the Adobe Acrobat Reader, please contact me.

-

I have not yet figured out how to determine the colorspace of JPEG2000 files. Therefore JPEG2000 files use DeviceRGB by default. For JPEG2000 files with other colorspaces, you must explicitly specify it using the

--colorspaceoption. -

Input images with alpha channels are not allowed. PDF doesn't support alpha channels in images and thus, the alpha channel of the input would have to be discarded. But img2pdf will always be lossless and thus, input images must not carry transparency information.

-

img2pdf uses PIL (or Pillow) to obtain image meta data and to convert the input if necessary. To prevent decompression bomb denial of service attacks, Pillow limits the maximum number of pixels an input image is allowed to have. If you are sure that you know what you are doing, then you can disable this safeguard by passing the

--pillow-limit-breakoption to img2pdf. This allows one to process even very large input images.

Installation

On a Debian- and Ubuntu-based systems, img2pdf can be installed from the official repositories:

$ apt install img2pdf

If you want to install it using pip, you can run:

$ pip3 install img2pdf

If you prefer to install from source code use:

$ cd img2pdf/

$ pip3 install .

To test the console script without installing the package on your system, use virtualenv:

$ cd img2pdf/

$ virtualenv ve

$ ve/bin/pip3 install .

You can then test the converter using:

$ ve/bin/img2pdf -o test.pdf src/tests/test.jpg

For Microsoft Windows users, PyInstaller based .exe files are produced by appveyor. If you don't want to install Python before using img2pdf you can head to appveyor and click on "Artifacts" to download the latest version: https://ci.appveyor.com/project/josch/img2pdf

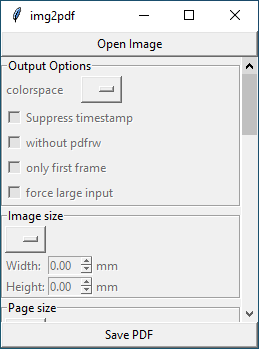

GUI

There exists an experimental GUI with all settings currently disabled. You can directly convert images to PDF but you cannot set any options via the GUI yet. If you are interested in adding more features to the PDF, please submit a merge request. The GUI is based on tkinter and works on Linux, Windows and MacOS.

Library

The package can also be used as a library:

import img2pdf

# opening from filename

with open("name.pdf","wb") as f:

f.write(img2pdf.convert('test.jpg'))

# opening from file handle

with open("name.pdf","wb") as f1, open("test.jpg") as f2:

f1.write(img2pdf.convert(f2))

# using in-memory image data

with open("name.pdf","wb") as f:

f.write(img2pdf.convert("\x89PNG...")

# multiple inputs (variant 1)

with open("name.pdf","wb") as f:

f.write(img2pdf.convert("test1.jpg", "test2.png"))

# multiple inputs (variant 2)

with open("name.pdf","wb") as f:

f.write(img2pdf.convert(["test1.jpg", "test2.png"]))

# convert all files ending in .jpg inside a directory

dirname = "/path/to/images"

with open("name.pdf","wb") as f:

imgs = []

for fname in os.listdir(dirname):

if not fname.endswith(".jpg"):

continue

path = os.path.join(dirname, fname)

if os.path.isdir(path):

continue

imgs.append(path)

f.write(img2pdf.convert(imgs))

# convert all files ending in .jpg in a directory and its subdirectories

dirname = "/path/to/images"

with open("name.pdf","wb") as f:

imgs = []

for r, _, f in os.walk(dirname):

for fname in f:

if not fname.endswith(".jpg"):

continue

imgs.append(os.path.join(r, fname))

f.write(img2pdf.convert(imgs))

# convert all files matching a glob

import glob

with open("name.pdf","wb") as f:

f.write(img2pdf.convert(glob.glob("/path/to/*.jpg")))

# writing to file descriptor

with open("name.pdf","wb") as f1, open("test.jpg") as f2:

img2pdf.convert(f2, outputstream=f1)

# specify paper size (A4)

a4inpt = (img2pdf.mm_to_pt(210),img2pdf.mm_to_pt(297))

layout_fun = img2pdf.get_layout_fun(a4inpt)

with open("name.pdf","wb") as f:

f.write(img2pdf.convert('test.jpg', layout_fun=layout_fun))

Comparison to ImageMagick

Create a large test image:

$ convert logo: -resize 8000x original.jpg

Convert it into PDF using ImageMagick and img2pdf:

$ time img2pdf original.jpg -o img2pdf.pdf

$ time convert original.jpg imagemagick.pdf

Notice how ImageMagick took an order of magnitude longer to do the conversion than img2pdf. It also used twice the memory.

Now extract the image data from both PDF documents and compare it to the original:

$ pdfimages -all img2pdf.pdf tmp

$ compare -metric AE original.jpg tmp-000.jpg null:

0

$ pdfimages -all imagemagick.pdf tmp

$ compare -metric AE original.jpg tmp-000.jpg null:

118716

To get lossless output with ImageMagick we can use Zip compression but that unnecessarily increases the size of the output:

$ convert original.jpg -compress Zip imagemagick.pdf

$ pdfimages -all imagemagick.pdf tmp

$ compare -metric AE original.jpg tmp-000.png null:

0

$ stat --format="%s %n" original.jpg img2pdf.pdf imagemagick.pdf

1535837 original.jpg

1536683 img2pdf.pdf

9397809 imagemagick.pdf

Comparison to pdfLaTeX

pdfLaTeX performs a lossless conversion from included images to PDF by default. If the input is a JPEG, then it simply embeds the JPEG into the PDF in the same way as img2pdf does it. But for other image formats it uses flate compression of the plain pixel data and thus needlessly increases the output file size:

$ convert logo: -resize 8000x original.png

$ cat << END > pdflatex.tex

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{graphicx}

\begin{document}

\includegraphics{original.png}

\end{document}

END

$ pdflatex pdflatex.tex

$ stat --format="%s %n" original.png pdflatex.pdf

4500182 original.png

9318120 pdflatex.pdf

Comparison to podofoimg2pdf

Like pdfLaTeX, podofoimg2pdf is able to perform a lossless conversion from JPEG to PDF by plainly embedding the JPEG data into the pdf container. But just like pdfLaTeX it uses flate compression for all other file formats, thus sometimes resulting in larger files than necessary.

$ convert logo: -resize 8000x original.png

$ podofoimg2pdf out.pdf original.png

stat --format="%s %n" original.png out.pdf

4500181 original.png

9335629 out.pdf

It also only supports JPEG, PNG and TIF as input and lacks many of the convenience features of img2pdf like page sizes, borders, rotation and metadata.

Comparison to Tesseract OCR

Tesseract OCR comes closest to the functionality img2pdf provides. It is able to convert JPEG and PNG input to PDF without needlessly increasing the filesize and is at the same time lossless. So if your input is JPEG and PNG images, then you should safely be able to use Tesseract instead of img2pdf. For other input, Tesseract might not do a lossless conversion. For example it converts CMYK input to RGB and removes the alpha channel from images with transparency. For multipage TIFF or animated GIF, it will only convert the first frame.